February 5, 2016, was a very bad day for shareholders of LinkedIn…

You’re likely familiar with the product. The employment-oriented social-media site was founded in 2003 and went public in May 2011.

The company listed shares at $45. But on its very first day of trading, the stock closed over 100% higher. The stock continued to be popular through the rest of the year. The company’s fourth-quarter earnings for 2011 saw revenue double year over year.

For a while, things were great. Then they weren’t…

On February 5, 2016, the stock plummeted 40%, erasing approximately $10 billion in market capitalization. The culprit was poor guidance for the upcoming quarter. The top- and bottom-line forecasts were well below analyst expectations. But the company’s fortunes were about to turn.

On June 13 that same year, the stock soared 48% in a single day. It wasn’t that the company’s fundamentals had turned around. It was much simpler.

Somebody had stepped up to buy it.

That was the day that Microsoft (MSFT) announced its intention to acquire LinkedIn in an all-cash $26.2 billion acquisition. It was among the biggest acquisitions at the time.

Stories like the one-day move for LinkedIn aren’t that uncommon.

Amazon (AMZN) famously bought Whole Foods, resulting in a one-day 27% gain for the grocery chain. Anheuser-Busch shareholders enjoyed a 35% instant gain thanks to InBev (BUD).

It’s not just public companies. The company previously known as Facebook (META) gave Instagram’s private shareholders a 100-plus times return when the social-media giant bought the company in 2012.

Anybody who held shares in the acquired companies mentioned above saw an instant repricing of their investment higher. That’s always a nice surprise to wake up to.

I mention this because it looks very likely that we’re on the edge of a new wave of mergers and acquisitions (M&A).

A Short History of M&A

The idea of M&A isn’t new. In fact, it’s centuries old.

The late 1800s was the first wave. Industrial titans combined steel, oil, and rail companies into the giants that powered America’s rise to the top of the global economy.

By the 1960s, conglomerates began to take over. These were mega-sized companies that took M&A to the next level. Instead of just vertically integrating like during the first wave, they bought companies in unrelated industries to diversify and grow even larger.

Firms like Gulf + Western would be a good example for this period. A business originally specializing in auto parts eventually expanded into sugar, mining, and even movie production.

The “Wolf of Wall Street” era of the 1980s was the next stage. Corporate raiders were born and powered by the invention of the high-yield “junk” bond market to fund their deals. Most of the famous Wall Street shops were created in this period.

Since 2000, technology has been in the spotlight. Companies like Alphabet (GOOG), Microsoft, Facebook/Meta, and many others have spent record amounts of capital buying out peers and expanding into new businesses.

All of this matters because, as mentioned above, any investors holding shares in the acquired company can see one-day returns in the 20% to 50% range as the market prices in the deal. That’s because a company usually only agrees to be acquired if it’s at a premium to the current market value of the stock… usually a significant one.

And it’s not just the targets that benefit. Huge companies with great balance sheets can acquire valuable intellectual property and top-caliber employees via acquisitions for far less than it would cost to replicate on their own.

The Facebook/Instagram deal is a good example of this. Facebook spent $1 billion to acquire the photo-sharing app. That seemed like an enormous sum at the time, but it was money well spent.

In 2024, it’s estimated that Instagram was responsible $66.9 billion in revenue, or 40% of Meta’s total haul that year. Done right, it really is a win-win.

Why I Believe M&A Is Coming Back with a Vengeance

In each case, these M&A “bull markets” were powered by unique factors. But the most important thing was what they had in common: cheap money.

Whether it’s the invention of the junk bond market in the 1980s, the leveraged buyout boom, or the zero-rate environment we all lived through more recently, people need cheap money to fuel M&A.

And judging by the latest announcement from the Federal Reserve, it looks like money is going to get cheaper.

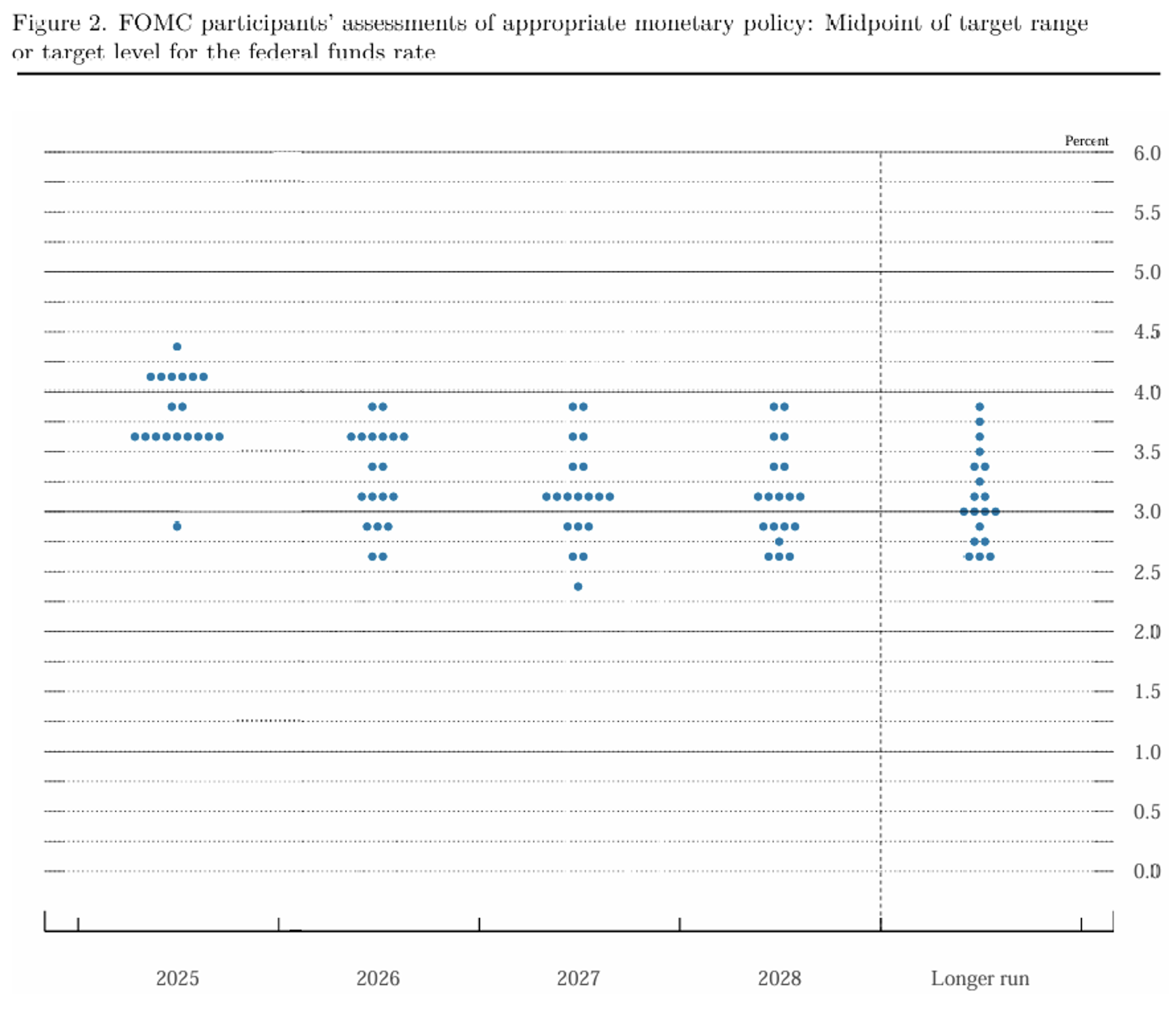

Source: Summary of Economic Projections. Federal Reserve.

This is called the Federal Reserve’s dot plot. At a high level, it shows the opinion of each Federal Open Market Committee member (the Fed’s governing body) on the trajectory of the Fed’s key rate over time.

Pay attention to the thickest lines, which represent more votes for that interest-rate level. You can see how most board members believe interest rates will fall at least a full point in the next couple years. That was kicked off earlier this week by the 0.25% rate cut.

There has already been a healthy amount of M&A this year.

In May, Dick’s Sporting Goods acquired Foot Locker for $2.4 billion. Last month, Skydance Media and Paramount Global completed an $8.4 billion merger. There’s now rumors that the combined company might also be eyeing Warner Bros. Discovery. And as my colleague Nick Ward shared with readers of The Wide Moat Letter, there’s an $85 billion mega-deal between rail giants Union Pacific and Norfolk Southern in the works.

I expect deals to accelerate as interest rates fall. Just like with the residential real estate market, cheaper money means more deal activity.

What You Can Do as an Investor

Fortunately, you don’t need to predict every buyout. Even the brightest minds on Wall Street can’t do that. Here’s how you can stack the odds in your favor:

-

Find industries ripe for consolidation. Right now, companies involved in electric vehicles, energy infrastructure, data centers, and biotech are hot.

-

Own quality companies at attractive valuations: Overpriced companies don’t earn large buyout premiums. And low-quality companies rarely get acquired at all.

-

Pay attention to the cost of capital. Not all companies will benefit from lower rates equally. Those that achieve a lower cost of capital first will be in the best position.

If any subscribers are looking for resources to help potential buyout targets, Brad and Nick share several potential candidates in the pages of The Wide Moat Letter and Wide Moat Confidential.

Brad in particular has an incredible track record of predicting M&A deals in the real estate investment trust (“REIT”) space. That’s because he lives and breathes the industry and knows exactly what drives consolidation.

All it takes is some old-fashioned due diligence with a little luck thrown in.

Regards,

Stephen Hester

Chief Analyst, Wide Moat Research

|